Return of the River – The Glen Canyon Story – May 25 Webcast at 6:00 p.m.

By Janet Welch

The "mega drought" impacting the Southwest is a tragedy, a travesty, and--in one way--a dream come true. The tragedy is the devastation being wrecked on the soil, plant. and animal ecosystems which have limited ability to adapt quickly enough to withstand the temperatures and water loss that are making an obviously harsh climate even harsher. The travesty is that humans are acting as if they can either wait out the problem or engineer solutions that will maintain existing lifestyles and economic systems that depend on watered fields, pastures, and lawns and embrace continued population growth.

The dream come true of the drought is a not-so-tiny sliver lining called Glen Canyon. With the flooding of Lake Powell behind the Glen Canyon Dam in the 60's, hundreds of miles of canyons, cultural sites, and riparian ecosystems were drowned. It has been called “America’s most regretted environmental mistake” and the failure to prevent it shifted the strategies and tactics of the environmental movement. Like some others, I only became aware of what was being lost while the waters were rising. For decades I have fantasized over the monkeywrenching that could destroy the dam and resurrect Glen Canyon.

The drought is bringing Glen Canyon back. The forces of nature are far greater than the huge plug of concrete. Lake Powell is at less than 30% capacity and may soon drop below the level at which the dam can produce electricity. The 200-mile-long reservoir of Lake Powell is dropping in elevation, but more significantly it is shrinking in size. As it shrinks, tributaries that were flooded for miles under the dead waters of the full reservoir are re-emerging.

The river is returning as portions of the Colorado River in Cataract Canyon and now increasingly downstream settle back into their historic channels. Rapids and riffles once again let water play where it had lain stuporous in the reservoir. Even more dramatic, however, are the hundreds of side canyons being exposed by the shrinking footprint of the reservoir. Even the sediment layers that had dropped out where stream flows hit the stagnant water of the reservoir are being swept clean in flash floods.

This amazing change is not going unnoticed. The Glen Canyon Institute, among others, is convening scientific field work to document this unique geological event that is occurring in the human timeframe. The restoration of riparian vegetation, scouring of sediments, and re-emergence of cultural and historical treasures are occurring in a mere blink of geologic time.

Want to learn more about this encouraging development? Oregonians for Wild Utah and Washington Friends of Wild Utah together with Southern Utah Wilderness Alliance are hosting a webcast “Return of the River: The Story of Glen Canyon,” featuring Jack Stauss, Outreach Director of the Glen Canyon Institute, on May 25 from 6:00 to 7:00 pm, Jack will share about one the largest unplanned ecological restorations in the world. Register in advance for this meeting:

https://us02web.zoom.us/meeting/register/tZMufuqoqzMjHtLy570UhBiDkv_wwLtu3Jx5

After registering, you will receive a confirmation email containing information about joining the meeting.

Janet grew up in Phoenix and her love for the wilderness was kindled at a young age in the canyons of the Colorado Plateau. Having spent her adult life living near the Canadian border, that passion for the plateau takes her back there nearly as often as to the seas and mountains much closer to home. Her lifelong dream of seeing Glen Canyon might yet come true.

A Sense of Place: Echo Park, Dinosaur National Monument

- Dick Little / www.ariversjourney.com

Echo Park felt like the center of the Universe, where the veil between earthbound reality and the eternal world of spiritual truth seemed thin as a cobweb.

Echo Park isn’t even in Utah, it’s in Colorado. Dinosaur National Monument, of which it’s a part, merely sticks its nose into the Beehive State, and in the northeast corner at that, far from SUWA land. That said, I’ll claim a place for it in this blog regardless since it is where I was baptized into the Southwest faith, where it claimed part of my soul.*

One bright summer day, from rolling sage and mesquite and occasional clumps of pinyon on a plateau in northwest Colorado, I began a hellish one-thousand-foot descent—thirteen miles in first gear over washboards and gullies, sometimes careening, then skidding to a stop and sending a cloud of dust and rocks over into an abyss. My uncomplaining truck clutched and braked, from time to time wanting to test its tipping point.

On we went, creeping and tumbling and inching down anew until at last we emerged into a quiet and majestic riverside park—a broad expanse of rolling gardenscape of juniper and box elder and deer brush surrounded on three sides by thousand-foot cliffs. The towering monolith of Steamboat Rock loomed straight ahead, its brawny arms, several million years’ worth of red-stained sandstone, crossed over its massive chest like a colossus.

I set up camp. I staked down my blue two-person tent, tossed in a pillow and sleeping bag, set my camp stove on a fire pit grate, and strung a white rope between two thin pines for shade. Over it, I hung my ever-so-handy orange rain poncho as the weather pattern started to change. Earlier, it’d been hot and still. Later, the wind picked up, loud on its way, before I even felt the gusts. It tunneled down from the mesas far above and swept into the valley floor. A minute later, a different gust sliced up from the river, caught me broadside, and I swayed for a moment like a drunk in a crosswalk.

Just as quickly, the wind stopped, and the midday desert sun disappeared behind a flotilla of black clouds. Like an alien spacecraft, the dark mass paraded overhead—advance guard, it turned out, for an even larger and darker mother ship of cumulonimbus that appeared from behind the escarpment. The cloud mass paused, gauged my insignificance, then drifted on in the ephemeral and unfocused way of clouds.

More than a visual message, Echo Park is history and prehistory. This was the place of refuge John Wesley Powell found and christened in 1869 after surviving the treacherous Lodore Canyon upstream on the Green River. His party rested here before moving on through Whirlpool Canyon and the improbable gorge of Split Mountain downriver. Major Powell’s epic journey of course made history and made his name. Miles downstream from where I sat and not on any map Powell had, the Grand Canyon waited.

At Echo Park, the veteran who fought with Grant at Shiloh rested by a fire and stirred his beans with his only arm. He mopped the broth with sourdough and listened to his men bounce their voices off the canyon walls. Next day, the troop put in and went off down the West’s most adventurous river. A century and a half later, I relaxed amid the scent of sun-warmed boulders and cottonwood. Powell’s presence in Echo Park felt as real as a slapped mosquito.

Before Powell, General William Ashley’s party floated the Lodore chasm in bullboats—dried buffalo hides stretched over willow branches, keelless, rudderless—on the downstream run, as unwieldy as steamer trunks. Ashley hauled out by a rock wall, climbed it, and inscribed “Ashley 1825” in black letters. Powell spotted the graffiti some forty-five years later.

In 1776, Fathers Dominguez and Escalante had sought a way west from Santa Fe, by then a town over 150 years old, to California. They followed the Old Spanish Trail which veered north in order to skirt the Grand Canyon. The intrepid padres continued up the Green River past the present city by that name in Utah, and the party crossed the Green not far below Echo Park where the spent stream flattens out. They named the river “Rio Buenaventura” believing it to be the rumored westward passage flowing to the Pacific. The myth held until the 1840s when John C. Frémont proved conclusively that there was no such waterway.

Before these seekers of Spanish fortune and Catholic converts, the resident Crow and Shoshone called the river the “Seeds-ke-dee Agie,” Prairie Hen River. It is worth noting that today the once-abundant prairie hens cannot be found anywhere nearer the Green River than isolated populations far to the east in Kansas. A scant nine of the thirty species of fish in the Green are indigenous; tamarisk and cheatgrass crowd out native horsetail and other riparians faster than they can be checked. Native chokecherry, box elder, and cottonwood are also threatened.

Lost to recorded time, a thousand years earlier, a people archeologists call the Fremont Culture knew the oasis at the confluence of the Green and Yampa rivers. Watched over by the Steamboat Rock massif, they farmed using irrigation techniques, grew corn, beans, and squash, and feasted on berries and cactus fruits and piñon nuts. They hunted wild game such as mule deer, bighorn sheep, small mammals, and birds.

High on the surrounding canyon walls, they created petroglyphs and pictographs, spiritual language I hoped to hear if I listened carefully.

In our time, Echo Park stands as a monument to the efforts of an aroused citizenry. In the 1950s, urged on by the likes of Bernard DeVoto, Wallace Stegner, and the Sierra Club, the Federal government’s attempt to dam the Yampa and Green Rivers was stopped in its tracks. The tragedy would have been profound, Echo Park submerged forever. The efforts to save other places that have failed (Glen Canyon, Hetch Hetchy) tear at the heart in places like Dinosaur all the more because of how nearly the battle there might have been lost.

But my presence—yours and everyone’s—presents a paradox: staggering natural beauty and timeless messages, essences of a place, are not reckoned, let alone understood and wondered at, other than by the very humans who encounter them and, even innocently or barely perceptibly, begin their despoliation. As Stegner observed, places are not places except as our senses take them in. Yet it is we who have often destroyed them or allowed them to be compromised. In my imagination, I even summoned up a boat; I’d shove off and live a childhood dream of running the Colorado with Powell—map my "experience onto a waking dream," in the words of Jonathan Franzen.

As it was, needing more than to understand but to actually feel Echo Park, I hiked and hiked, sand tugging at my boots, using both hands to brush aside tall grass, enjoying the feel of sage branches scratching my face as I squeezed past them.

At night, I’d lie in my tent alert to every sound, every snap of a twig, every nighthawk's bzzt, every whisper of a breeze, every rustle of some night creature. At some point, sleep happened, and I’d awaken refreshed and hungry. A lazy breakfast—bacon of course, eggs and hash, firepit-charred toast, and camp coffee—watching the sun paint the top reaches of Steamboat Rock and start to climb the taller pines in the valley.

But back to Stegner’s paradox. Was my presence there purchased at a price I might decide I should no longer be willing to pay? I subsisted in timeless Echo Park by virtue of meals concocted out of foil packets; a plastic bottle made from petroleum polymers; a tent, fly, tarp, ground cover, sleeping bag, and mattress (also jacket, daypack, and boots) made of state-of-the-art nylon, polyester, or Gortex; and, tent poles, canteen, lantern, camera, binoculars and camp stove (with throw-away propane canister), made of aluminum or even more exotic materials at who-knows-what environmental cost in extracting, smelting, and molding. I drove here in a truck that gets lousy mileage.

Without these things, would I even be here? Should humankind simply not invade this space?

I lay down in my shorts and t-shirt on top of the concrete picnic table by my tent, arms and legs akimbo, and stared straight up into an endless sky. I listened to warblers, buntings, swallows, sparrows, towhees and the scree of a hawk. I heard no people. Tiny wisps of campfire smoke teased my nostrils. The languid breeze was warm.

I would stay there forever, I decided. I would not solve good Professor Stegner’s problem in a week. I placed the blame elsewhere: in spite of itself, Echo Park was its own worst enemy.

I stretched. My solitude and the grace bestowed upon me was the result of no little denial, to be sure. But this I banished into the silence and the stories that surrounded me. I closed my eyes, and off I went into the eternity of rivers and rock escarpments and lost languages, and the truth of my transience.

…round apples glowing red in the orchard and the rustle of the leaves make me pause to think how many other than human forces affect us… I respond – how?

Virginia Woolf - “A Sketch of the Past”

*See, however, Canyon County Updates (Summer 2021), “BLM Resurrects Dinosaur Area Drilling Proposal.”

Birch Hollow

- Max Feingold

It is the first year of the plague. A few days into a socially distanced road trip, on a pleasant morning in late June, my wife Ella and I are descending Birch Hollow. We are learning to canyoneer, and this is our first serious technical canyon.

We park the Jeep at a small trailhead on a dirt road, somewhere above the massive Orderville Canyon drainage, just on the edge of Zion National Park. There is one vehicle already parked here, likely early bird canyoneers. A Bureau of Land Management sign regales us with dire warnings advising us to avoid doing what we’re about to do.

On the way here, North Fork Road took us through a peculiar mixture of cattle farms, sprawling resorts, and some very high-end housing. It is easy to forget how small Zion is: from this oddly developed area, a raven could fly just a couple of miles east and find itself another tourist in the Virgin River Narrows.

We gear up and prepare for a long day. The technical section is near the end of the canyon, where it tumbles dramatically into Orderville. We have a few miles to stroll before harnessing up and breaking out the ropes.

The approach is not, in fact, a stroll in the park. It is a winding tramp through brush, up and down and around on uneven terrain. The canyon walls begin a chalky white, not yet the sculptural sandstone they will become.

One last house on a hill to the west overlooks the hollow. More houses are scattered through the forest to the east, just out of sight. Roads crisscross the area, connecting clearcuts like a cancerous nervous system. Like much of the Southwest, here the land is either protected or it will metastasize.

A half mile in, we cross the invisible boundary into the Orderville Canyon Wilderness Study Area. As if on cue, nature becomes red at tooth and claw. Four desiccated mule deer legs are scattered across the trail, separated by some force of nature, mummifying slowly in the wash. Soon we find a ribcage, pale white and stripped of flesh. This is mountain lion territory, and here we have a crime scene.

Abruptly, the trail comes to an end. A large limestone bowl yawns beneath us, invitingly circular, with a sharp overhang and a good sixty-foot drop to the bottom. There is a canyoneering anchor attached to a boulder slightly upstream, in good condition and ready for use. This is the way.

We apply the skills we’ve learned. Two one-hundred-and-twenty-foot ropes, threaded through the quicklink. A double overhand knot makes a connection. A triple clove hitch solidifies a carabiner block. One side for descending, another for recovery.

One of us will have to go first. For a moment, neither of us moves.

I clip into the rappel rope and approach the edge. Weight on the rope, progress locked, I glance over the edge into the abyss. Sixty feet up, I am a bird on the wind.

First, a downclimb onto a small ledge, where a gentle flow of water slips through the layers. Then a crouch down over an overhung lip, nothing but air beneath me, nowhere to go but down.

Dripping rock curves inward. The rope slides into position at the lip. Gravity beckons. I begin a free hang rappel towards the ground, still distant. A miniature waterfall drips gently onto my helmet and shoulders. At the scariest moment I feel an elation, a joyful sense of belonging. Any remaining fear evaporates and becomes certainty. I will become a competent canyoneer today; there are simply no other options.

Friction controls velocity. The rope flows just right. Trust the rope, and the tools. Balance. Down to another ledge, then I’m on my feet at the bottom of the bowl. The ride ends just a little too soon.

Ella follows, tentatively over the edge at first, then a graceful glide path down. At some point in the air and under the spray she realizes she’s having a great time. As she joins me at the bottom she is beaming.

Tentatively I begin the recovery process, using the pull side of the block. The rope slides down smoothly, falling in a pile at our feet. Step one complete.

Downstream, the canyon slots up and begins to narrow. We encounter a few simple obstacles and descend three very straightforward rappels, anchored off metal bolts affixed to gray sandstone walls.

The narrows open into a forested area, ponderosa pines growing out of sand. We eat lunch at a pleasant spot above a chasm in the earth, a hundred feet straight down. This is the sixth rappel.

We drop rope from an anchor attached to a large tree, set back from the edge of the dryfall. Carabiner block at the anchor, an awkward start, a beautiful carved flute below. Ella descends first. I follow. Smooth sandstone all the way down, ropes converging up to the sky.

At the bottom, I pick up the pull rope and give it a tug. No movement at all.

I shake the pull rope, then shake the rappel rope. I walk backward and try again. I shake the rope harder, cascading waves of fury to no avail. I put all my weight on the pull side. I yank with all my strength. I hang from the rope. I slap the wall in frustration.

The rope is stuck and will not come down.

The slot around us is stunningly beautiful, yellow and orange tones creeping into gray sandstone. Downcanyon we can see the next anchor, nicely bolted above a fifty-foot drop. There is no way out.

Nights can be cold here, even in late June. We have water and a few remaining snacks. No flashlights, warm clothes, or emergency blankets. We may have come unprepared.

It is very quiet for a moment. But there are options.

It is possible someone will come along and release our rope from above. This is a trade route, as canyons go. We’ve been slow. Someone will catch up.

I do have a satellite device in my backpack, able to call search and rescue. For many reasons, this is not the answer. We should be able to handle this kind of situation ourselves.

It is time to use another tool in our arsenal. I cut some webbing and tie myself a loop. I attach an ascender and a progress capture device to the rappel rope. Two attachment points now. Carabiner in the ascender, loop in the carabiner, foot in the loop. Guide slack rope through the carabiner to obtain some mechanical advantage.

I begin my ascent. Stand up, shifting weight to the foot loop, while pulling on the slack rope: the lower attachment point rises. Lean back, shifting weight to the progress capture device, while sliding the ascender further up the rope: the upper attachment point rises. Rinse and repeat.

Suddenly I’m five feet in the air, gradually rising. Only ninety-five feet to go.

It is a workout, like riding a bicycle up a wall while hanging in the air.

At twenty-five feet the vertigo kicks in, but I look up and keep going. I aim for small victories: the next indentation, that discoloration in the chute. The top of the rappel is still very far away. At fifty feet I stop to rest. Ella is very small on the canyon floor. She shouts encouragement and seems mildly bemused that I’ve managed to get this far.

By the time I reach the top of the flute, muscles I’ve never heard of are achy and sore. I grab the rope above the lip and pull myself onto solid ground, gasping like a flounder at the edge of an abyss. I rest for a minute and rise to inspect the ropes.

I see no problem at all. Nothing is stuck.

I call down to Ella to test the rope pull. No problem. I must have dislodged the rope from a rope groove as I climbed up. Grooves are the devil. But this is on us: we forgot to test the rope pull before descending. Valuable lesson learned.

A breathless rappel later, I gingerly grasp the pull rope. For a heart-stopping microsecond, I pull. Harder.

Then the carabiner block comes free at the anchor and the rope slides gracefully down and we are saved. I will not have to ascend again.

The next few rappels come fast and furious. We count a total of ten before the end. The last two are postcard-worthy descents into stunning sandstone chambers, temples to the nameless canyoneering gods. Here in the heart of the wilderness, in a place only a few people have seen, it all feels worth it.

A few more steps and we’re blinking in harsh afternoon sunlight, the outside air ten degrees warmer. We emerge as if from a dry birthing place into Orderville Canyon. It’s time to pay the piper and regain the fifteen hundred feet we just lost.

Two turns upcanyon and we spot the path up. There are several ways out, Wild Wind Hollow being the fastest, the driest, and the steepest: just a mile and a half, but straight up with no respite.

We ascend through all the geological layers very quickly, then climb steeply through a pleasant ponderosa pine forest, rising far above Orderville until it is but a small discontinuity below us. We climb a steep segment up to a hogback ridge, then keep following that ridge up and up and up. We see the Zion canyons in the distance to the southeast, Orderville slotting up near the Narrows. We see forested hills and meadows up towards the Markagunt Plateau.

We chug water and hope it will last us. We eat granola bars and agree to always test the rope pull. We slog along, and curse rope grooves. We are tired.

Gradually the wilderness gives way to the familiar. We see the last house on the hill. We see a campground and suddenly everything levels off. The trailhead is a short distance away, and there we find our Jeep.

There are no other cars at the trailhead. We were the last group into Birch Hollow today.

Return to Bear’s Ears

- Janet Welch

This spring, as Covid lockdown requirements loosened, my husband Willi and I drove to Utah for a month of hiking and exploring. I had been in the Bear's Ears area in the late 70's when I was splitting my time between living on the Colorado Plateau and Washington. It was time to go back.

When Willi and I became a couple 25 years ago we agreed that he'd take me ocean sailing and I'd take him to Utah. He fulfilled his promise about 6 years before I fulfilled mine, but I eventually introduced him to Escalante. We spent a month exploring the many places that weren't accessible to me when I had passed through on my bike many years earlier. We only sailed to Mexico once, but Utah has pulled us back 3 times since his first trip.

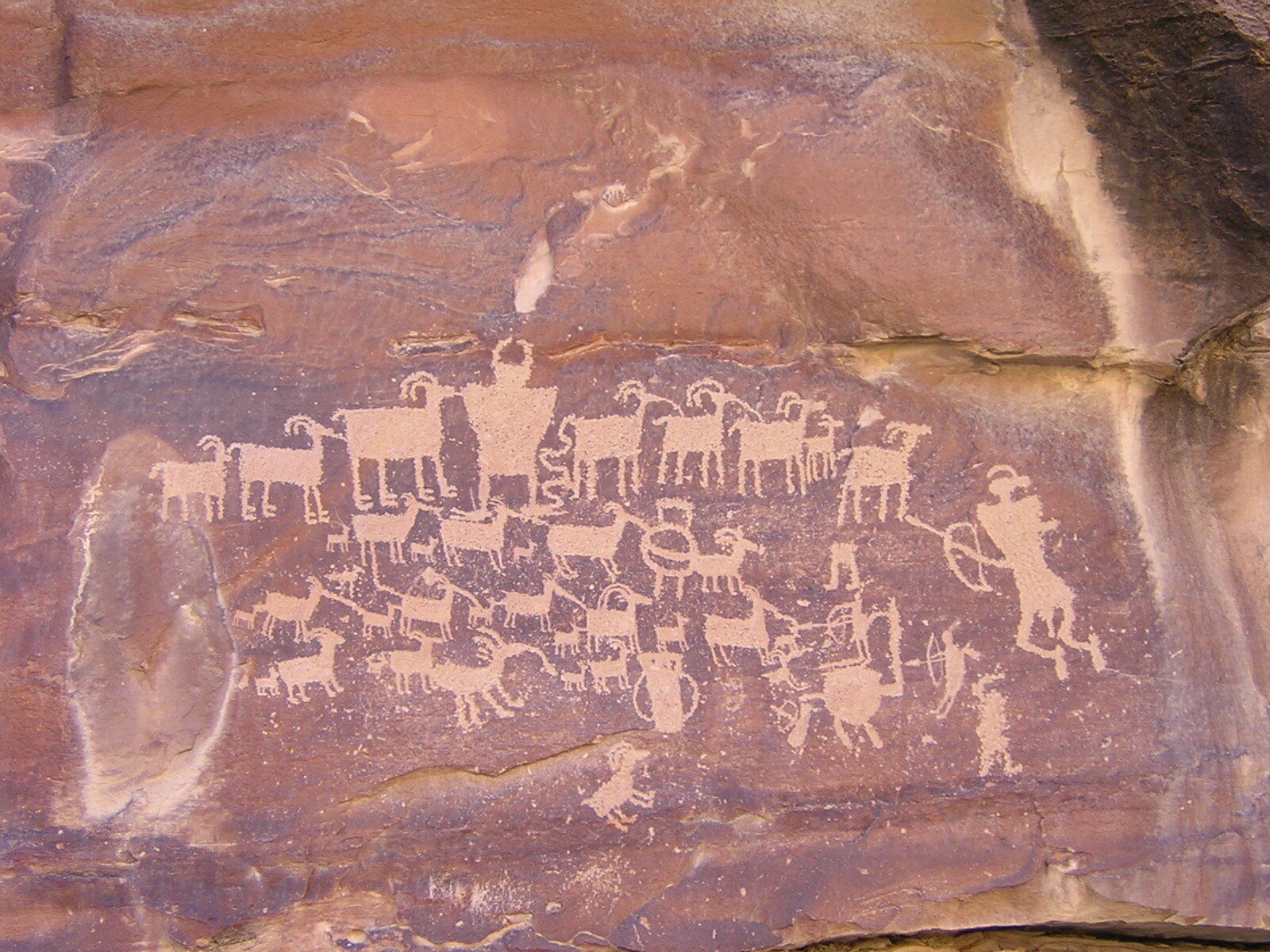

It was hard to convince him to visit someplace new, since we love Escalante so much, but you wouldn't know that now. He loved the rock art! Before we left we read up on the culture of the Ancient Ones (the term which has largely replaced "Anasazi"), and its demise, and about pottery and rock art. Many theories had evolved since my days on the Plateau fifty years ago, including theories about their 'disappearance' and documentation that their history in the area extends back multiple millenia further than once thought.

Still, nothing prepared us for the daily experience of 'discovering' the ruins and rock art evidence of that culture on our hikes. In avoiding the popular destinations, our hikes were unscripted, with no expectations as to what we might find. We prefer to be surprised by a small find rather than promised a great one. We were richly rewarded.

For a month we wandered and explored and clambered and backtracked and pondered. Our pondering repeatedly circled back to the move of the Ancient Ones into defensible cliffside structures, prior to their eventual 'disappearance'.

Back in the 70's I led walks around a ruin at a little museum at the Grand Canyon. There, I explained that the vital culture had fought over increasingly scarce resources (water and arable land) before ultimately being destroyed by a multi-year drought. I talked by rote, feeling oddly detached from the knowledge. Having grown up in Phoenix, my assumption was that engineers had vanquished the threat of drought, just as medicine had vanquished the threat of infection. But like antibiotic resistance that has restored the risk of infection, nature is reminding us that the culture that collapsed in the 1300's due to drought might not be the last one.

The Southwest is in what they are calling a 'mega-drought'. The sleight of hand that promised more water than the capacity of the Colorado River has been revealed for the wishful thinking that it was. Everything from alfalfa fields in the Arizona desert to the Vegas strip, from lettuce growers in the Imperial Valley to the sprawling megalopoli in five states will be affected by increasingly dire water shortages. A person doesn't need to call it 'climate change' to know that forests and grasslands, and the homes of people and animals who live there, are burning.

Hmmm, the culture of the Ancient Ones was destroyed by climate change. They killed their neighbors over diminishing resources and retreated to the cliffs in defense. Their culture fractured over diminishing resources. They didn't 'disappear', but rather became climate refugees, moving to the south and elsewhere in search of water. They probably begged, or fought, communities to let them stay. Individuals clearly survived but the whole of the culture didn't.

Walking among the remains of the Ancient Ones culture, Willi and I recognized history's repeat performance and how those ruins probably foretell the impending consequences of the world's failure to live within its means and its blindness to curbing carbon emissions before it was too late.

Drilling for Natural Gas in the World’s Longest Art Gallery

~ Valerie Monsey

Mark and I had been looking forward to our visit to Nine Mile Canyon in central Utah in the summer of 2006. We have been visiting Utah's remote and beautiful canyon country regularly since falling in love with this part of the world many, many years ago. Our favorite activity is hiking in the canyons, where the solitude and stunning natural beauty provide a much needed respite from living and working in Seattle. The trip to Nine Mile Canyon was to include one of our favorite activities, searching for rock art sites.

Nine Mile Canyon, which is actually 40 miles long, is often called the “world's longest art gallery”, and is supposed to contain over 10,000 petroglyphs, pictographs, and prehistoric archaeological sites. It is thought that the Archaic people lived in the canyon 8000 years ago, the Fremont people about 2500 years ago, and more recently the Ute people made it their home. A road through the canyon was constructed in the late 1880's, and historic sites including the ghost town of Harper remain.

We have visited Utah many times, and are well versed in how to “visit with respect”, including not touching any rock art (petroglyphs and pictographs), and not disturbing any archaeological sites that you come across. Some of these sites could be a thousand years old, and we like to think that maybe a thousand years from now people will still be able to experience the wonder of stumbling onto rock art sites and ancient ruins while exploring remote canyons.

Our plan was to spend an enjoyable day driving slowly up the narrow, winding, gravel road, binoculars and guide book in hand, searching for rock art and ancient granaries in the canyon walls. We planned to set up our tent and camp on public land outside of the canyon area, and then spend a second day exploring.

What we didn't know at the time was that the U.S. Bureau of Land Management (BLM), who manages most of the land in the canyon, had recently granted drilling rights in the West Tavaputs Plateau to the Bill Barrett Corporation (BBC), and that Nine Mile Canyon was now a primary access route for this major industrial operation, with a plan to drill up to 800 gas wells.

It didn't take long for us to realize our mistake. Speed limit signs in the canyon posted by BBC made it clear that this special place that contemporary tribes value as a place of spiritual heritage was now an industrial zone. A sign targeting BBC personnel and contractors stated that the speed limit was 20 mph and 10 mph on corners due to heavy truck traffic, and "VIOLATORS WILL BE TERMINATED".

Our next clue was the tanker trucks. A convoy of tanker trucks worked it's way down from a side road ahead of us, filling the canyon with dust. We speculated on what they could be for. Maybe they were water trucks being used to spray the road to keep the dust down? Small sections of road were wet, but it did nothing to stop the clouds of fine dust from filling the air. We were not impressed.

We drove past a large industrial building located on the far side of the canyon. Loud, booming sounds emanated from the building. We had no idea what it was, but figured it was something to do with the drilling operations. It was definitely not peaceful.

Next were the contractors in their pickup trucks. There were many blind corners on this gravel road, and it soon became clear that the contractors did not expect to see traffic. We avoided a head-on collision by stopping before a blind corner as we could hear a truck coming. The truck came racing around the corner, saw us, and slammed on the brakes, skidding to a stop in the gravel. We learned to stop and pull over when we heard a vehicle coming. Our expectation of a peaceful day exploring the canyon turned into a white knuckled driving experience as it was clear it was up to us to avoid a collision. No one was even close to following the posted speed limits.

Next was the tanker truck upside down in a creek that was right next to the road. Another truck was stopped there, but we didn't know what the driver was doing and he wasn't interested in talking to us. We took a closer look after the second truck left. The truck in the creek was coated in dust. How long had it been there? How could it happen? Were vehicle fluids getting into the creek, the only water source for miles around?

Finally we came across several large tanks next to the creek. Diesel from the generator had spilled onto the ground with no effort to clean it up. Abandoned vehicle batteries lay dumped on the ground. There were no spill cleanup materials anywhere around.

The dangerous driving conditions made us abandon our trip early. We just wanted to get out of there. It was so disappointing to see how this amazing place was being treated. I always remember that trip when I hear about proposed oil and gas drilling operations, and how oil and gas companies say they can be good stewards of the environment. I'm not opposed to all drilling. My house is heated with natural gas. But what was happening in Nine Mile Canyon was wrong.

When I decided to write this post, I did some online research to see how Nine Mile Canyon has been doing since that trip. I learned that this area has been the subject of countless appeals and lawsuits regarding the potential impacts from proposed oil and gas drilling in the area.

The National Trust for Historic Preservation included Nine Mile Canyon on it's list of "America's Most Endangered Places" in 2004. An archeologist at the local Bureau of Land Management office who voiced concern over the potential significant impacts to the canyon's rock art was barred from conducting any oversight of the project. Online newsletters posted by the Nine Mile Canyon Coalition, a nonprofit group created in the 1990's advocating for the preservation and protection of the canyon, document thousands of hours of effort in working with the BLM towards this goal.

The conditions we observed on our trip apparently continued to get worse, and by 2008 the lawsuits were continuing. A scientist documented that magnesium chloride, which was being used as a dust suppressant, was coating rock art sites.

The Nine Mile Canyon Coalition noted in a 2010 newsletter that what the BBC called "minor seepage" was an ongoing leak from a compressor that had been going on for at least a year. The spill was discovered when a truck driver noticed a sheen on Nine Mile Creek. I learned that there was an explosion and fire at the Dry Canyon natural gas compressor facility in 2012, which I think is the noisy building we observed in 2006.

Finally a formal agreement was made in 2010 that was a compromise between a coalition of conservation groups, including SUWA, and state and local agencies. This document requires that the BBC conduct extensive mitigation and restoration work, and reduced the overall scope of the development. The road through the canyon was paved in 2013. I found a letter prepared by The Nine Mile Canyon Coalition in 2016 protesting an oil and gas lease sale. The August 2020 Newsletter notes that "the coalition and several partners protested and requested a review of a particularly bad BLM decision on gas drilling that would have had major impacts on Nine Mile Canyon".

This research has made it even more clear to me how incredibly important the tireless efforts of volunteers and conservation groups are in protecting our public lands.

The battle to save Nine Mile Canyon continues.

Opening

Washington Friends Wild Utah

Janet Welch

by: Janet Welch

Naturally formed or manmade? Exploring the slickrock of southern Utah's canyon country, we were walking the swirling patterns of ancient sand dunes, watchful to avoid the delicate cryptogamic (biologically complex) soils. We had been here before, an easily accessed and navigated watershed that had been one of our favorites for its waterfalls, sculpted iron rich rock formations, intriguing plant communities, and expanses of cross bedded sandstone.

A few days before, exploring a few miles away we had crossed tracks with some locals. They were as surprised to see us as we were them, since we steer clear of guidebook attractions and the ubiquitous GPS guided visitors. Chatting about 'favorite spots' we mentioned the nearby watershed. "Have you found the cave?" was their response. Unspoken were directions or details. We didn't ask, and they didn't offer. We like it that way.

Intrigued by the idea of finding a minute feature like a cave in the expanses of that amazing country, a few days later we dropped into the canyon.

On a previous visit, we had traversed a slope on a seam between the layers of crossbedding that had piqued my husband's attention. "Hmmm, this almost looks manmade..." We discussed it briefly and didn't think much more of it; crossbedding is like that. This time we found ourselves at the same spot and when the memory returned to us we gave it more consideration. A short distance later we paused to enjoy a lovely little overlook where we'd been the previous time.

One of the finest things about exploring the wilds of Utah is the opportunity to open. To open to the deep blue sky, or maybe the biting cold wind, the minute wildflower hidden in a rock crevice, the sound of cottonwood or aspen leaves fluttering. The grandest opportunity, however, is to open to the expanse, the perfect topographic result of eons of time. Thus reflecting on that expanse, we realized that something was different. The crossbedding pattern continued, but with a different roughness. We backtracked a hundred yards and saw a barely perceptible sheen to the rock that veered from the naturally formed joint in the crossbedding. We traversed down the slope for 20 feet and found ourselves directly below where we had just stood, looking into the cave.

This place, not far from the headwaters of the creek that had formed the canyon, was obviously a well used camping place for the ancient ones (and, alas, ranchers who also left their mark). Cooking fires had blackened the overhead and art still graced the walls. How long ago had the first person found the easy route across the slope, dropped to the stream bed to get water and discovered the cave? How many feet had worn that crossbedded joint through the centuries that their culture thrived there?

We opened even further that day, not only to the plants, the color of the sky and the biting of the wind. We realized that maybe the grandest opportunity is opening beyond the expanse of terrain, to the expansiveness of time. Linked across the centuries, that day we encountered the locals just as vividly as our experience just a few days before.

Photos: Willi Smothers

Zebra Slot, 2021

Washington Friends Wild Utah

by: Michael Little

The author, between the rocks

Last Sunday I woke up just outside Escalante, Utah. My traveling companion a bike builder, data analyst I’ve known since college. We pulled off of Highway 12, having sped through the Dixie National Forest mostly in the dark, pointing out the vistas I remembered from the drive last year, however imperceptible they were in the night. We tucked in for sleep near the entrance of the Hole in the Rock Road, wanting to get some solid sleep ahead of the hike into Zebra Slot the next morning.

This was my friend’s first time in Utah. An avid Pacific Northwesterner he spends his time in Washington and southern California. We woke up the morning prior on the banks of the Colorado, outside Moab, staring up at that giant red rock face.

How to describe Grand Staircase Escalante National Monument to someone for the first time. It is a park, yes. Well, sort of. There is no park entrance, no fee to be paid, no rangers per se. A vast swath of Southwestern Utah roughly the size of Delaware. Protected ecology, riverbeds, waterfalls, hoodoos, mountainscapes: all true.

Also true: this 1-million plus acres was halved in the Trump era, for the sake of mining and access roads. Imagine criss-crossing dirt roads, turbinate smokestacks smouldering, the shudder and hull of heavy machines, specious caterwaul.

For now, GSENM remains protected under President Bill Clinton’s designation as a national monument in 1996.

Cracking open the van door into the brisk February morning sunlight, I was again reminded of how I felt the first time I turned my car south out of Moab and into this otherworld.

I had spent the previous two decades in New York. Two summers ago, my partner and I decided we were going to leave the City and head west. We drove two days, from New York to Moab. August, triple-digit heat. We had a tent, sleeping bags, hiking boots. We bought scones from Moonflower Coop in Moab, and hit the trails running. Having put nearly 2,000 miles between us and our past lives, we trod out into the ochre and red rocks wide-eyed, inspired. I remember staring up at the rock face at Goose Island campground, across the frigid Colorado, and thinking to myself: this is a skyscraper.

After days of arches and afternoons in the river, with blistered feet, hands pumiced by sandstone, we turned toward Highway 12 and Grand Staircase, 2019.

The gym near my office in midtown upgraded their treadmills the year before I left New York. Three or four days a week I would duck out of a meeting and jog to the gym and workout in lieu of lunch. Usually 45 minutes, shower and back to the office. The new treadmills were perfect. I am a runner. I run. Preferably trails. And in the place of trails, I could now log into a treadmill and select a trail to have projected on the screen in front of me. The treadmill would flex and akimbo to match the recorded elevation changes of the track - trail - I was on, which had been previously videoed by a now-vistitant runner. Sydney Waterfront (populated with animatronic tourists posing for pictures), Rome (Colosseum, etc. etc.), Pebble Beach (golfers, fog).

The course I was most intrigued in was titled simply: Grand Staircase. On the screen: backpacked hikers, a dog or two gracefully moved aside as the ersatz “you” jogged down a sandstone ravine. A creek at the bottom and then jog up and back to some kind of red-rock rim: five miles. I would run Grand Staircase enough times each week I got to know the turns, the fauna.

And when we decided we were heading West, I pinned Grand Staircase to the itinerary.

However, herein lies the problem. Where to pin? An excess of one million acres of a square on a map. The map I was working off of was shades of brown. The section of the park labeled GSENM: a too-milky-coffee hue.

My partner made reservations at a campsite just outside Canonville. Greeted by the camp steward (a Marine Biology instructor at Humboldt State University) and his Labrador, Lozen, we looked like first-timers with our New York license plates, overpriced camping gear and hyper-idiomatic speech. At this point we had acquired enough red dust to buy us a second look with the masses, however any conversation longer than two sentences and our former lives quickly betrayed us.

We stayed three days: Kodachrome Basin (“Shakespeare Arch has fallen”), Bryce Canyon (hoodoos), Capitol Reef (Fruita), Willis Creek Canyon (three men entombed in a pickup trapped in Bull Valley Gorge). Each day we would hike, climb or run these trails and return to our camp, cook vegan hot dogs, and pass out. Night #two or #three the steward told us about Hell’s Backbone Grill.

Fast Forward to now. The van door slides open. Just across from where we parked a Neapolitan cliffside of Tropic Shale, Dakota Formation, Navajo Sandstone. Snow-tipped pines like abandoned sentry dot the hillside. My friend and I put on our shoes and walk into the open range toward the slot. This time no overpriced gear and my drawl has been Westernized these past months. It is February, however, and we struggle to keep moving fast enough to outpace the cold.

Not a cloud in the sky.

Before long we’d descended 300 feet. Into a wash or gulch or dry riverbed. The sun warming us overhead, the only sound for miles: our footsteps on the softsand and rockbasin.

And like the Grand Staircase of my gym-going days, our descent is amid red-rocks, sand, sandstone worn round by millenia of wind erosion. Knee-high rabbitbrush, sagebrush, cacti. There are no other hikers on the path today, no dogs. We march off into the brown and burnt green and red which surrounds us at every vista.

According to the map, Zebra slot is named for the striations on the rockwall in the slot. However, Zebra striations begin well outside the slot entrance. I continue to be stunned by the silence, the stillness. One mile in we sidestep a cattle fence and step into the soft sand of Harris Wash.

As prescribed, we leave all our excess gear at the mouth of the slot, tucked behind a desert shrub. There is no water this time of year. My friend and I strip down to our base layers and make our way into the void.

Not far into the chasm the slot narrows to a mere ten inches. Perhaps the walls up to the rim of the canyon are seventy-five feet. Perhaps more. The friend I am traveling with races outrigger canoes - mostly he is all back muscle and arms. I am still at hibernation weight. Between our two visages ten inches might as well be no inch.

At the tightest juncture we strip down further. I inch into the pinching rock walls. At my best I am able to split the gap by exhaling completely and shimmying an inch or two up using my pelvis and scraping my chest through. Between the rock I pause, and considering the year it’s been, the silence around me, the fact I can see the Zebra on the rock walls - do I need to touch/feel it? Actually? Do i? - my lungs completely collapse and pin me between two layers of rock one-hundred times older than my father’s father’s bloodline. Again I notice the silence. Nothing is moving.

And I remain in this place for some seconds. Able to breathe by taking small sips of air.

“I’m going around,” my friend shouts from the entrance - he’d retreated to put some layers back on.

I slide out.

We walk out and up and over the top of the slot to look down onto the zebra walls. Perhaps another twenty feet in from where we turned around the cave dead-ends. And the look down from where we were is no less stunning.

Atop the cavern I notice balls of rocks collected in deeper basins. Now completely dry these balls have been hewn into perfect circles by the little rain that falls here, perhaps once, maybe twice, each year in large enough volume to puddle and stream down the ravine. The rocks sit unmoved in the basin of a dried-out watering hole, like fossil eggs.

The Buddha is said to have expressed time in units called Kalpas. According to the Buddha there is a mountain sixteen miles high, and once every 100 years a bird flies over the peak with a piece of silk in its beak and lightly swipes the top of the rock. One Kalpa is the length of time it will take for the entire mountain to be eroded by the scarf.

And how many Kalpas to attain enlightenment? Perhaps these riverworn rocks know.

The two miles hike back to the car my friend and I talk about the effort, and lunch. Mostly the effort: Did we fail not going all the way? Should I have brought rope? Should we have skipped that second or third taco last night? Was there something deeper in the slot we had missed?

We pass two hikers on the trail as we are headed out. The first people we have seen all day. The couple is from Minnesota. They have matching NorthFace parkas. Between the two of them, ten inches will come easily.

They say this is their first time in Utah. I remember the one winter I spent outside St. Paul, temperatures I had only read about existing.

“It’s going to be great,” I offer as they turn and bounce down the trail toward the zebras.